What drew you to studying African photography and its history?

I had a general interest in photography from an early age on but it was undirected; just a fascination for the photographic image and the possibilities the camera offered to see and communicate with the world. There was even a moment when I wanted to become a professional photographer but I was and still am not a good photographer. I tell you this because together with an interest in African history I developed as a university student it prepared me for what was to become my epyphany so to speak, which surprisingly was not the huge photo archives of the Basel Mission in my hometown and its charismatic archivist Paul Jenkins but the moment when I opened the pages of Carl Passavant’s photo albums.

Passavant, a medical doctor from Basel, had traveled to West and Central Africa twice in the 1880s and brought back some 250 photographs from these trips. In the early 2000s, we still believed that Passavant had taken the photographs. This quickly turned out to be a mistake, because what we had in our hands with the albums, we realized, was a survey of the work of African photographers in West and Central Africa before 1880. This was, and still is, quite unique. So, here a door opened that showed a section of African reality that otherwise was not accessible.

Well, that’s quite a bit of historiography, but you have to understand that at that time there was both a lack of interest in photographs as sources by historians or anthropologists, and a general lack of awareness that African photographers were active in this region as early as the 1860s. Sure, researchers like Vera Widitz-Ward had already unearthed and written about early Westafrican photographers in the mid-1980s and Chris Geary argued in the same years “A potentially fruitful area of research on photography in Africa has been almost totally ignored: photography by Africans, including the role of African photographers in early photography”. Look how much that has changed! So there was a lot to do, and a group of dedicated researchers on this side and the other side of the Atlantic formed, researching the topic and exchanging ideas with each other. It was exciting, and still is.

In your writings, you describe the significance of political and journalistic photographs for scholars who are engaged in the study of the history of Africa. Could you tell us a little bit more about some of the obstacles these researchers face in trying to source these photographs?

In Africa, as everywhere else in the world, the researcher interested in photographic sources is dependent on people and institutions who take care of the material, grant access to it and keep order. There are collections that are quite well kept and protected, but the archivist sees his main task as preventing any contact between the researcher and the material; you are simply considered a nuisance. Sometimes you don’t know who to turn to for access to a specific collection, sometimes the archives are in such a desolate state that any search is futile. I would not say that the biggest problems one encounters when it comes to issues of access to political and journalistic photos is that it is restricted, prevented or limited for political or censorship reasons. Rather, one is dealing with limited resources, regarding infrastructure and personnel, as well as with gross neglect and disinterest. However, there are always surprises in all directions.

How did photography in Western and Central Africa begin?

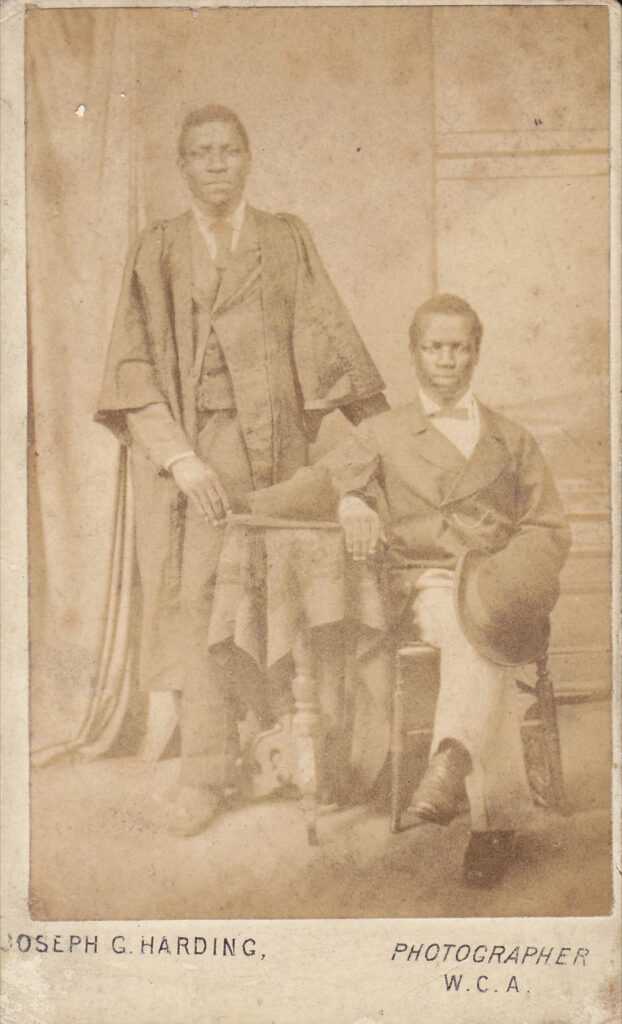

Europeans were the first to travel with a camera to the region. In the early 1840s there were the French French Navy captain Louis Édouard Bouët-Willaumez and a French traveller named Jules Itier. The latter was a member of the Lagrené Mission, the first French diplomatic mission to China. Ten years later, the African-American daguerreotypist Augustus Washington settled in Liberia and continued his profession there. In the mid 1850s the British missionary Daniel West visited the Gold Coast, today Ghana, and in the 1860s more and more missionaries were equipped with cameras when they were sent to the „field“. You see the pattern: With the exception of Augustus Washington the early photographers in Western and Central Africa were missionaries and the military. The first African-born photographers became active in the mid-1860s. In most cases, they were itinerant, some part time photographers who traveled along the coast, making longer or shorter stops in port cities such as Cape Town, Lagos or Freetown when the potential clientele was large enough and worth a stay. Another feature of these early photographers was their British, in most cases, or other European family names, such as Decker, Johnson, Johnston, May, Lewis, Lutterodt or Joaque, a fact which for some time, for us researchers, obscured their African identity. Furthermore, most of these early photographers hailed from the British West African settlements, Gambia, Sierra Leone, Cold Coast and Nigeria but their radius of operation included the whole West coast down to Angola. I emphasize coast because for a long time the activity of photographers was largely limited to the coastal region. They worked for traders, passing travellers and adventurers, misionaries, the colonial administration and the local, African mission-educated elite who had quickly integrated photographs in their Victorian lifstyle. So you see, technical or business skills was one key factor for the spread of photography in the region but as important were the social practises that needed to be developped, in short the question what one was to do with a photograph.

Do you have a favourite photograph/photographer from this early period?

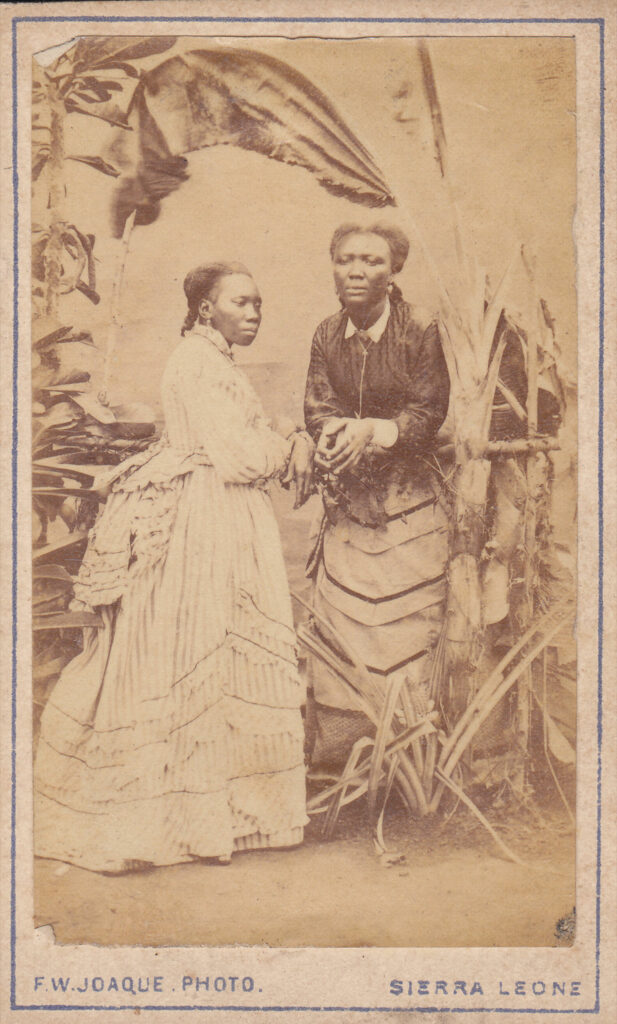

Oh yes! It is Francis W. Joaque. The man was born in Freetown, Sierra Leone around 1840. Between 1865 and 1890 he run studios in Sierra Leone, Fernando Po (today Bioko, Equatorial Guinea) and Libreville, Gabon, before returning to Freetown, so he moved a lot during his live.

The quality of his photographs is outstanding and after so much time I spent with him, doing research on him, I can tell with high accuracy if a photograph is a Joaque or not. Technically, he is superb; just imagine for a moment what it meant to take a photograph in the tropics at that time. He was still working with wet plates. He had a highly developed sense for harmony and balance of composition. He was innovative. There are very very few stereoscopic photographs from that region and time, but he made some. We have even a portrait of him which shows him standing behind a stereo camera. He must have liked music since he played the piano and harmonium as various souces tell us. And, looking at his business logos on the back of his photographs, he had a sense of humor and wit. I mean, he was all but the half naked black photographer depicted there.

In your study of early Western and Central Africa, you refer to the notion of the “Atlantic visualscape” when describing the flow and exchange of images across national borders. How does this concept pertain to the early stages of photography on the continent?

In my dissertation and some of my subsequent publications I developped the idea that accelerating flows of migration within a triangle encompassing West Africa, the eastern tip of Brazil, further north British Guyana and some Caribbean islands as well as Great Britain, and the accompanying changes in social relationships, which now had to re-establish themselves over further distances in space and time, offered photography a crucial task and position. Photographs made absent people present in a way that was unimaginable before photography, a medium that was considered, with regard to is representational qualities, highly trustfull. It’s all about „facework“, to borrow that term from the English sociologist Anthony Giddens. I further compared photographs in this context with money, a visual currency, which as money circulated, could be exchanged and was based on trust. The idea of trust is key here.

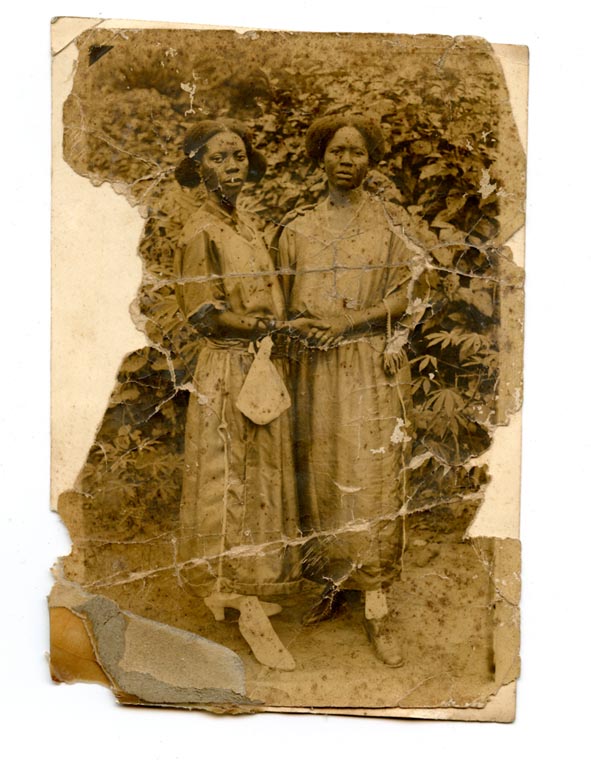

Photographs were indeed very mobile, as was a part of the population, admittedly numerically a relatively small group, and it was these people who circulated photographs, as prints – of family members, friends, business partners, lovers, etc. – in various formats but also as reproductions in books and illustrated magazines. There were for instance families in Lagos whose members lived on both side of the Antlantic who shared the same family photographs. There were as well families whose members lived in different places on the coast. Carte de visite were exchanged between friends and business partners. I found one from British Guyana in the possession of a British pailm oil trader in the Niger delta. Joaque produced a substantial series of carte de visite of Mpongwe women from libreville who had a reputation among Whites for their beauty, and also for their willingness to engage with Whites. These photographs were commissioned either by the women or the men, in any case to keep in touch visually and in remembrance for good times passed. There were so many ways, means and media to keep photographs in the Atlantic visualscape afloat.

Could you tell us a little about how photographs became a powerful vehicle for a colonial or “Anglophone” agenda?

Let me answer more broadly and talk rather about the colonial agenda of European powers in Africa in general. There is quite a bit of research that has been done in recent years on the crucial role photographs played in the exploration and subsequent subjugation of the continent; most prominently James Ryan’s Picturing Empire (1997), Paul Landau and Deborah Kaspin’s Images and Empires (2002) or Leila Koivunen’s Visualizing Africa in 19th-Century British Travel Accounts (2009).

Now, who were the protagonists of the colonial agenda? And why would they be interested in photographs? Explorers, adventurers and traders prepared the ground for the colonial seizure of the continent. Christian missions were integral and integrating part of colonialism, colonial adminstrations together with its indigenous staff kept the colonial situation upright and alive. They all wanted and needed to „give a face“ to the peoples and places they were working with and in. Give a face in order to explain, visually, where they were, what they did and achieved and how the people looked like, to a short denominator, in order to secure support and sympathies in the metropole. The Missionary Leaves Association which provided the Church Missionary Society with harmoniums, equipment for lantern shows, etc., as from 1875 kept a Photo Specimen Book in circulation in Britain from which photographs from the CMS’s mission areas – pastors, communities, churches mainly in Nigeria and Sierra Leone – could be ordered as copies. Already some years earlier the British Colonial Offices had comissioned the African photographer John Parkes Decker to take photographs from its posessions in West Africa and to send them to London. A great example for photographs from the colonies as document and argument was the series of 14 photographs (taken by Joaque) the Spanish governor on Fernando Po, Diego Santisteban, sent to Madrid in the 1870s that were to bear visual and hence truthful evidence of the Spanish possession’s wealth and its inhabitant’s interest in the economic development of the island. This happened in a period when Spain’s interest in the small island off the Cameroonian coast was low and its withdrawing a political option. I wrote an article about the initiative of Santisteban, which I like very much because it was written in collaboration with a Spanish colleague and because, like the photographic tour of the capital Santa Isabel, it gives a well-rounded self-contained story that answers the opening question very nicely.

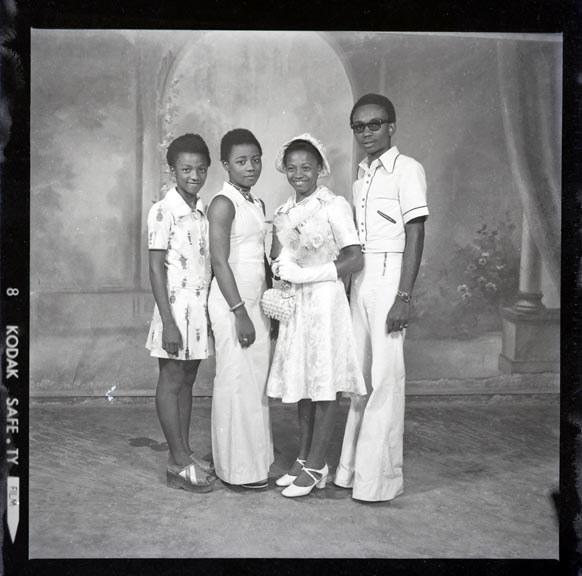

You have described the flamboyant backgrounds for portrait photographs in studios in Burundi’s suburbs Kamenge, Bwiza, Buyenzi or Cibitoke as if they are an ‘art form’; perhaps they render these photographs as ‘artistic’. Do you know of any art photographers from the time period you have studied or photographs that can be considered as ‘works of art’?

The German art historian Ernst Gombrich wrote in 1950 in the introduction to his History of Art, a book with immense influence on art history and art historiography, „There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists“. I would agree. I think that Art is made by and on the market and the museum. Telling to me is what happened to the photographs the Malian photographers Seydou Keita and Malik Sidibe took in the 1950s when they were „discovered“ by Susan Vogel and later André Magnin who worked for Jean Pigozzi. Prizes went up and the photographers started to sign their works, something they had not done before. And, they became artists, were made artists. Maybe they were african photo artists avant la lettre but I doubt they considered themselves artists, certainly not in the way the West defines it. I think this also describes the sitiuation in Burundi. There are always photographers with a higher aspiration for their work than others, those who practice their craft with a claim to perfection, harmony, balance. And in fact, many do succeed. Keita and Sidibe definitely belonge in this category. So, again, depending on your definition of art there were definitely photographs from these places and period that stand out from the masses of images produced that we could call „works of art“. Art photographers? Maybe, but to me rather skilled and gifted artisans.

Do you take photographs in the African countries that you study? If so, are there any insights you have derived from this practice that lends to your understanding and research?

I take photographs with my mobile phone, as I do everwhere on my travels, but forget them later and generally do not look at them again afterwards. And of course, I use photography to document the state of the archives we work with the work done there or in relation to it, so in the broadest sense I then use photography as a work documentation.

What is the current status of photography in the countries you have visited and studied?

Photography is constantly changing, both in terms of its material, technical dimension, and in terms of fashions and tastes. Smaller and more manageable cameras, color photography and digital photography have each triggered profound changes in consumer behavior and on the supply side. What once was affordable only to a small group of people has become the latest with the advent of smartphones, a medium of the masses. Television and the visual flattery of consumers with ever new goods and service offerings have also led to an inflationary world of images in West and Central Africa. The NGO world, with its demand for images, the increasing number of Photofestivals on the continent and in the West as well as the international art market with its still growing appetite for „African photography“ are also large consumers of photographs. But I doubt that this, over all, has created many more job opportunities for photographers. For sure, it certainly changed the demands placed on a photographer and created a new type: internationally networked, mobile, familiar with the new social media and the digital world. Some continue to run their photo studios, but many have closed in recent years or are no longer in operation. Most of the studios in Bujumbura, for example, that we visited around 2007 no longer exist. Why go to a photo studio for a passport photo, when you can get the same and faster on the street from one of the many ambulant photographers, who print the photos immediately. In short, like many other sectors of the economy, like many other professions, photography too has undergone massive change in recent decades, with some losing out and others seeing opportunities and seizing them.

But we cannot talk about the current status of photography without mentioning the archive, the archiving, storage and conservation of photographs, which in my opinion is one, if not the biggest challenge. On the one hand, the still existing analogue photo archives are endangered, there is a lack of interest, protection, personnel, infrastructure, you name it. On the other hand, we run the risk, already now, but certainly in the future, that a large part of digital photographs from the region will no longer exist. In another place I have spoken of a digital void. Why? Mainly because in the analog era, for various reasons, photographs were stored centrally in one place and they were accessible there in material form, as negatives and/or prints. If no major catastrophes such as fire or water damage destroyed the stocks, the material survived for a good while. In the digital age, there is a strong tendency for decentralized archiving of photographs, which requires permanent technical adjustments or reformatting for accessibility. And if the material is not additionally backed up somewhere else, then hardware crashes are fatal. How many photographers devote the necessary care and attention to this aspect of their work? How many institutions, governmental or non-governmental, have centrally managed photo archives?

What are your most treasured African photography book(s)?

The answer to this is not simple. First, what is an African photo book? And what is a photo book? But such ponderations put aside I can tell you which volumes come to my mind and its up to you then to tell me if these are African photo books. On the one hand, as a historian, I really like the books about photographs in and from Africa that Michael Graham-Stewart self-publishes from time to time. He is an British collector and dealer, deeply interested in the photographs and those who made them. At the same time he is a meticoulous researcher and generously shares his knowledge and the material he aquires with us scholars. Then, when we go beyond such basic research work and and the provision of research material, I am very much, and I would say, ultimately, interested in books where text and image unite. I mean books where the image becomes a better image, it is probably more accurate to say it becomes what it really is, because its inherent potential is set free by the text, and the text gains in depth and quality because it is written in communication with the image. David Goldblatt’s books come to my mind, On the Mines, for instance. And there is Terry Kurgan, like Goldblatt a South African, with her book project Everyone is Present, which I deeply admire. Although her book begins with a family snapshot made by her Polish grandfather in 1939 in Poland (Zakopane for those who know the place) on the eve of the war and ends with a photograph she took herself many years later in the same city I consider it an African photography book. Judge for yourself.

Do you have any current or future projects on the horizon?

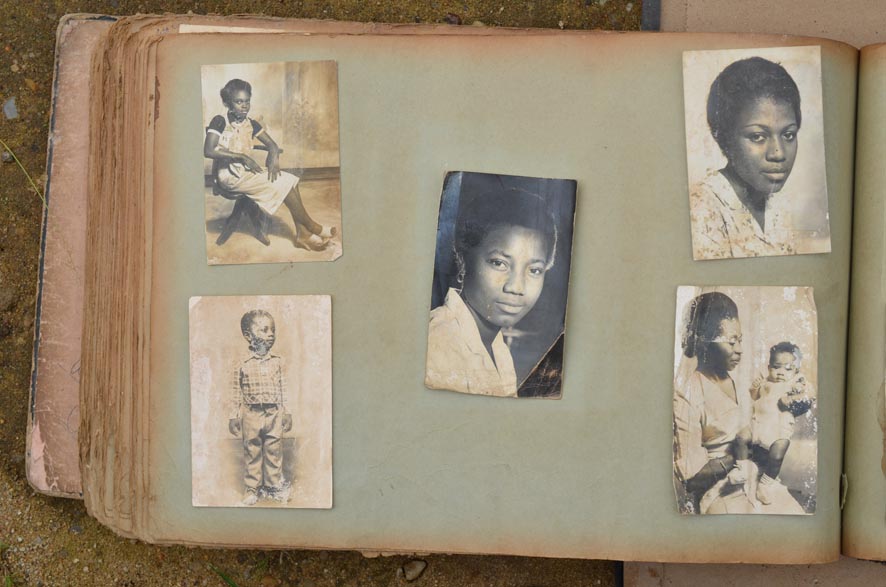

Apart from teaching, writing, reviewing and editing I am currently working on two main projects. One is research on two collections of family photographs from Cameroon. These collections, and families, are in various ways connected to each other, over time, places and people. Its about stories and the History of mobility, social and in space, in the period from the 1920s to the 1990s in Cameroon, France, Germany and the US. What I am mainly interested in, what drives me, is the question what one can do with old photographs, with photographs somebody took in the past and someone other deemed worth keeping. What happens when we take photographs, in this case two collections of photographs, which in the past for sure have undergone various changes, have seen additions and losses, „to think with“, to quote Elizabthe Edwards, and thus go beyond the narrow concept of „photographs as empirical, evidential inscriptions“? The other project is less photographic but somehow related to the first. This one too allows me to explore some new lands beyond the purely visual. It is a new edition of an autobiography of a Cameroonian who came in 1913 as a boy to Germany to continue his education. There he was confronted as much with friendship and love as with racism and disrespect. Its a very interesting work and unfortunately out of stock; a rare autobiographical source which skill- and artfully combines self-experience, reflections and Cameroonian folk tales. A bit further in the future I have plans to work on photo materials in Africa, paper, film, etc., the distribution and marketing strategies of the big brands like Kodak or Agfa. We will see where this will take me.